I was moved to write this after hearing Dr Lyla June of the Diné Nation speak at the Oxford Real Farming Conference earlier this month. She spoke of Indigenous peoples as the architects of abundance - cultures that did not simply live on the land, but shaped it into productive, biodiverse systems through careful observation and long memory. Alongside this, I have been guided by the work of Dr Jessica Hutchings, a Māori scholar who speaks of food systems grounded in kaitiakitanga - guardianship, responsibility, and relationship with land and water that stretches beyond individual ownership and into obligation to future generations. What both make clear is that abundance is never accidental. It is shaped by the choices we make, season after season, generation after generation.

Where we live, we are not short of rainfall, fertility, or growing potential. What we are increasingly short of is resilience. Winters saturate our soils, tracks soften into streams, nutrients slip from fields into waterways, and wildlife thins without us almost noticing. Walk the land after heavy rain and it tells you everything: where soil has shifted, where water has hurried, where roots were not strong enough to hold. What leaves our fields does not vanish. It moves into ditches, then streams, then rivers, like the Dalch — the river that runs adjacent to the farm — carrying our management with it. Farming and water are not separate stories. They are one long conversation, written in mud and flow.

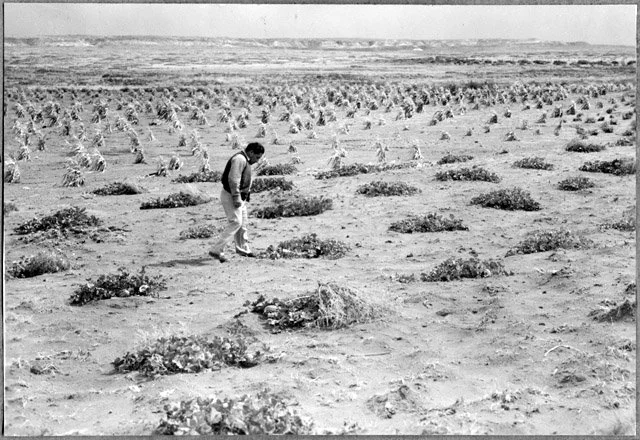

Indigenous land knowledge is often spoken of as spiritual or symbolic, but in truth it is precise, practical, and deeply ecological. Across the world, food systems were built on diversity, continuous ground cover, careful timing, and an intimate understanding of how water and soil behave together. These were not untouched wildernesses, but working landscapes shaped to support both people and the wider web of life. Dr Jessica Hutchings speaks of land and water as kin, and when you treat something as kin, your decisions shift. You do not extract without thought. You plan for endurance. Productivity is not abandoned, but placed inside responsibility.